Practical utopias: A creative methods workshop

Blog content

Affective and creative experimentation are ‘orchestrated yet unpredictable processes that activate the body’s ability to relate to, sense and imagine the world in new ways’ (Knudsen, Krogh and Stage 2022: Methodologies of Affective Experimentation: 1).

On 11th June 2025, members of the “Utopia and Failure” network joined Rebecca Coleman in a creative methods workshop. Rebecca is Professor in the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies at Bristol University. She led academics and researchers in a creative exercise of building utopias as part of a teach-out at Newcastle University. Against the backdrop of a Higher Education sector that is in crisis, with UCU strikes at Newcastle, people gathered in the local pub to create a space where it might be possible to engage in alternative utopian worldbuilding.

Here was a space to creatively construct possible ways out of failure.

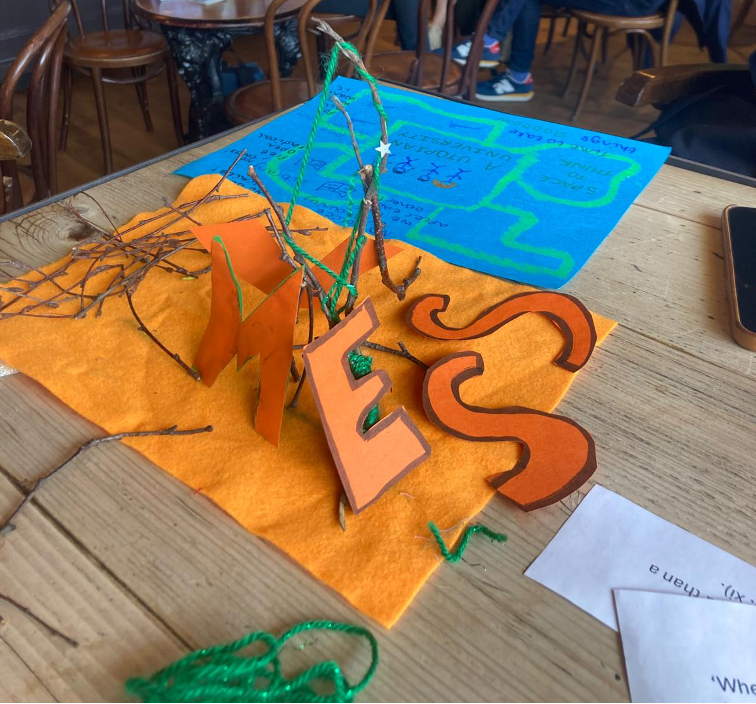

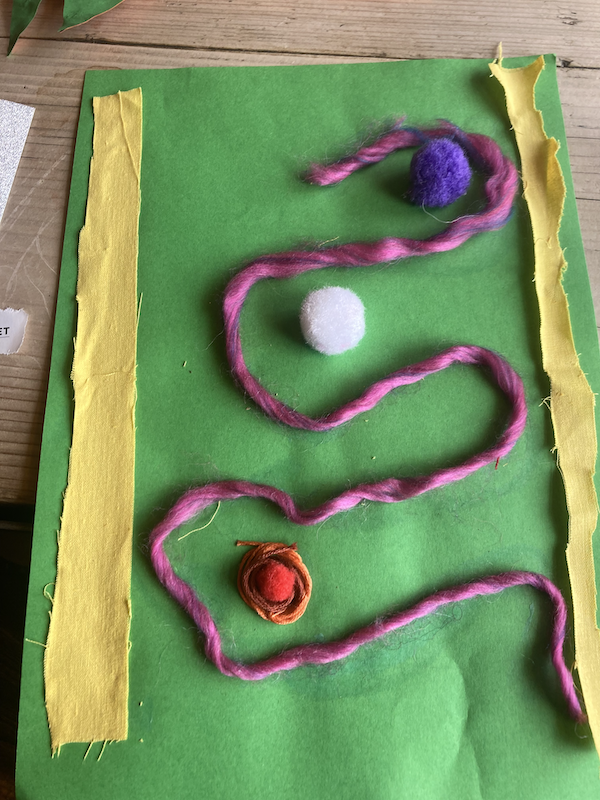

Armed with materials – paper, pens, glitter, magazines, fabrics, sticks and pompoms, amongst other items, Rebecca invited people to “get hands on with making something that articulates what a utopian future might look like, feel like”. Prompts in the form of quotations from some writers on futures and utopias were distributed for people to reflect on why utopian futures are necessary and how it might be possible to scaffold imaginations of better futures.

Below we share a lightly edited version of Rebecca’s introduction to the workshop alongside images of what some of the participants made. The main text is by Rebecca Coleman. Editorial comments and context by Ruth Houghton and Lisa Garforth (Newcastle University) in italics.

Notes on creative workshops and utopias

Rebecca Coleman.

The politics of imagining and making utopias and better futures.

For Rebecca, utopias and utopian thinking and methods are needed now more than ever – even if utopianism is a challenging and unstable concept.

Utopias are a contested terrain. There are many critiques of a focus on utopia – and futures more broadly – because they are seen as unachievable, as never reached and therefore as directing attention away from more urgent politics of the present. For example, through her conceptualisation of cruel optimism, Lauren Berlant problematises approaches that emphasise the future because ‘they enable a concept of the later to suspend questions about the cruelty of the now’ (2011: 28). Lee Edelman argues that queer theory needs to embrace a critical position of ‘no future’, which challenges a logic of heteronormative reproductive futurism and takes up the negativity of being outside of ‘generational succession, [linear] temporality, and narrative sequence’ (2004: 60).

Quotations used in the workshop, however, centred an alternative position.

It is necessary to continue to find ways to invest in things being different and better. Jose Esteban Munoz, for example, takes issue with Edelman’s rejection of futurity, arguing:

It is important not to hand over futurity to normative white reproductive futurity. That dominant mode of futurity is indeed “winning”, but that is all the more reason to call on a utopian political imagination that will enable us to glimpse another time and place: a “not-yet” where queer youths of color actually get to grow up (2009: 95-96).

As these debates demonstrate, the terrain of utopias and futures is contested because there is no agreement on how temporal politics work. Do they take us away from the difficulties (Berlant) and pleasures (Edelman) of the present, or do they focus on the need for change (Munoz)?

A focus on utopias and futures sets out how politics function temporally: by focusing on utopias, we can see the contested ground through which politics takes place through practices such as imagining, anticipating, hoping, pre-empting, planning and their synchronisation across different scales (institutional, personal…). Indeed, such an understanding of utopias sees futures as always in-the-making and therefore always in the present. Futures are ‘not-yet’ but at the same time are in constant relations of recalibration with the present, as Sarah Sharma puts it (2014), or as Adams et al put it in a discussion of anticipation, are ‘inhabited in the present’ as their anticipation ‘sets the conditions of possibility for action in the present’ (2009: 249).

Materials, materiality and getting hands-on

Rebecca’s research centres the material. A lot of the materials that Rebecca shared with the group were from different projects that she has been involved with, and the context or source of the materials was an important part of working with them. She brought magazines like those used in her PhD research on young women’s experiences of their bodies through images. There was glitter from collaging workshops where young women were asked to imagine their future. Rebecca has written a book on glitter, which followed glitter from mainstream girls’ culture to femininity, LGBTQ* protests and films about Black and mixed race women, reflecting on the politics of future making.

Getting hands-on with tactile materials can be a way to highlight the significance of understanding utopias not as a final destination but as an ongoing process – ‘utopia as method’ as Ruth Levitas (2013) puts it. It can focus attention on the perhaps unusual or unexpected things through which research can be and is done.

Rebecca recently co-edited How to Do Research With… (2024) with Kat Jungnickel and Nirmal Puwar. The book presents a guide to the doing of critical and creative research with a range of unusual means to apprise places and build ethical relationships.

The book tried to highlight the unusual and unexpected –often diverse and overlooked things and people; the weird and wonderful. How might we direct our attention to them? Working with materials can lead to unusual and unexpected outcomes. Broken twigs, dried up pens, ripped paper and card you can’t stick things to. It is in these “failures” or “glitches” that we can experiment.

The glitch ‘embraces the causality of “error”, and turns the gloomy implication of glitch on its ear by acknowledging that an error in a social system that has already disturbed by economic, racial, social, sexual and cultural stratification - may not, in fact, be an error at all, but rather a much needed erratum’ (2012, n.p.) and that can ‘provide [...] opportunity for queer propositions for new modalities of being and newly proposed worlds’

(Legacy Russell 2020 Glitch Feminism: 123).

Rebecca argues that working hands-on with materials can help provide generative responses to key methodological challenges in contemporary social research.

How do we bring more ‘craftiness’ (Les Back 2012) and inventiveness (Lury and Wakeford 2012) to research? This involves being critical, creative, interdisciplinary – turning critical attention to methods; being imaginative, inspired, inventive, crafty; learning from other disciplines, interfering with disciplinary boundaries, and possibly creating new fields?

Working with materials can also draw our attention to what matters to us in our imaginations of better futures, in our worldings. As Donna Haraway says, “It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories” (2016: 12).

Here, materials are affective, they engage our bodies as well as our minds in certain ways.

Fumbling with textiles, sharing scissors and glue-sticks, (re)building utopian structures and imaginaries, indeed working with materials in a creative workshop such as this was a way of exploring utopia as method.

Rebecca’s workshop took us out of our comfort zones in a thoughtful and supportive way and introduced a range of participants to the complexities and possibilities of working materially within a utopian framework.

Huge thanks: to Rebecca for pivoting rapidly and gracefully from preparing a conventional seminar to running a large teach-out in a noisy room; to those who attended and shared their creativity; to the Newcastle Sociology Pasts and Futures research cluster (especially Anselma Gallinat) and the NU Law School for their original support for Rebecca’s visit.